|

Works Cited

“Camp Alexander (1).” Camp Haan - FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts.“Camp Hill and Camp Alexander W-68.” Marker History, 22 Dec. 2011. “Certificate of Birth.” Indiana, Brazil, 5 Oct. 1918. Helen Elizabeth Morgan “Certificate of Birth.” Indiana, Indianapolis, 2 Dec. 1920. Willa May Morgan “Certificate of Birth.” Indiana, Indianapolis, 2 June 1922. Harold Morgan “Certificate of Birth.” Indiana, Indianapolis, 2 June 1922. Higby Morgan, Jr. “Certificate Of Birth.” Indiana, South Bend, 20 May 1924. Geraldine Morgan “Chapter XXII.” Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War, by Emmett Jay. Scott, Theclassics Us, 2013.

“Colored Men Are Wanted For Stevedore Enlistments.” Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel, 19 Sept. 1917.

“Company A, 301st Stevedore Regiment Cited.” Cayton's Weekly, 19 Oct. 1918. “Death Certificate.” Indiana, Indianapolis, 2 June 1922. Harold Morgan “Death Certificate.” Indiana, Indianapolis, 23 June 1923. Higby Morgan, Jr “Death Certificate.” Indiana, South Bend, 3 Apr. 1930. Higby Morgan “Death Certificatecate.” Indiana, Angola, 12 Dec. 2000. Geraldine Morgan “E.J.Scott. The American Negro in the World War. Illustrations, Chapter IX.” Sarajevo, June 28, 1914.

“Fifteen Colored Men To Report.” The Sentinel, 10 Apr. 1918. “Hampton Roads Area.” Fort Boykin Historical Website. “Higby Morgan In France.” The Sentinel, 2 Oct. 1918. "Indiana Marriages, 1780-1992," database, FamilySearch "Indiana Marriages, 1780-1992," database, FamilySearch, "Indiana Marriages, 1811-2007," database with images, FamilySearch Clark 1893-1894 Volume Q image 15 of 277; County clerk offices, Indiana.

“Is Now Across The Water.” The Sentinel, 5 July 1918. Leith, Rod. “Mystery Surrounding African American Veteran Somewhat Solved.” North Jersey, NorthJersey, 14 July 2017.

Marcosson, Isaac Frederick. S. O. S. America's Miracle in France. Nabu Press, 2010. McWhirter, Cameron. Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. St. Martin's Press, 2012.

“Miami County Men Enlisted For Service .” The Sentinel, 1 May 1918. National Museum of the United States Army. “FIGHTING FOR RESPECT:African-American Soldiers in WWI.”

The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States Army, The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States Army

Https://Armyhistory.org/Wp-Content/Uploads/2017/01/arty_1-Left-1024x786.Jpg, 15 Feb. 2018. “Now In France.” Peru Daily Chronical, 3 July 1918. “Office of Medical History.” Office of Medical History - Army Nurse Corps History, “Page 389.” South Bend City Directory, p. 389. “Passenger List.” Virginia, New Port News, 6 June 1918. Company C, 336 Labor Battalion, Ship Roster, includes Higby Morgan

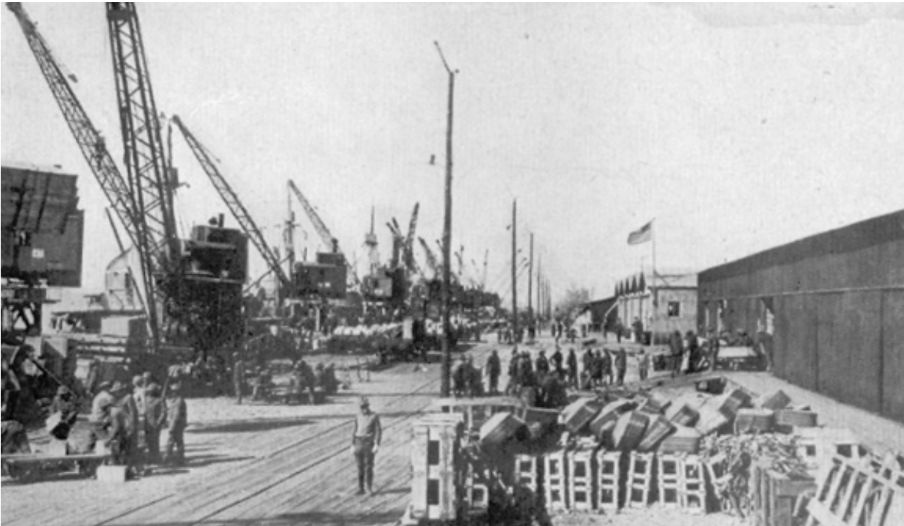

Port of Embarkation . Headquarters. Historical Record of Camp Alexander, Virginia, February 20, 1919. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and

University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries LOCATION

Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries MS 312 IDENTIFIER mums312-b014-i415 PERMALINK Http://Credo.library.umass.edu/View/Full/mums312-b014-i415.

“Re: Roster of 371st Infantry Regiment, WW1.” Runaway Slave Ads - Baltimore County, Maryland - 1842-1863.

“Selected Men Instructed by County Board.” Peru Journal, 21 Aug. 1918. “South Bend City Directory.” Indiana, South Bend, 1929. Page 508 “South Bend City Directory.” Indiana, South Bend, 1929. page 924 “Stevedore Operations, American Expeditionary Forces.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Feb. 2018,

Tutorials, Script. Black Soldiers Mattered. "United States Census, 1900," database with images, FamilySearch : (accessed 8 October 2018), Higgby Morgan in household of Clarence Morgan,

Jeffersonville Township Jeffersonville city Ward 1, Clark, Indiana, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 8, sheet 12B, family 257, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1972.); FHL microfilm 1,240,363. Image "United States Census, 1920," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 8 October 2018), Higby Morgan in household of Lillian Caison, Indianapolis Ward 5,

Marion, Indiana, United States; citing ED 109, sheet 8A, line 32, family 168, NARA

microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1992), roll 453; FHL microfilm 1,820,453. Image "United States Census, 1930," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 8 October 2018), Helen Morgan, South Bend, St Joseph, Indiana, United States;

citing enumeration district (ED) ED 21, sheet 12B, line 78, family 240, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 626; FHL microfilm 2,340,361. Image "United States Census, 1940," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 14 March 2018), Willa May Morgan in household of Daisy Dempsey, Ward 4,

South Bend, Portage Township, St. Joseph, Indiana, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 97-46, sheet 3B, line 58, family 62, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, NARA digital publication T627. Records of the Bureau of the Census, 1790 - 2007, RG 29. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012, roll 1134. Image "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch (Accessed : 13 March 2018), Higby Dedrick Morgan, 1917-1918; citing

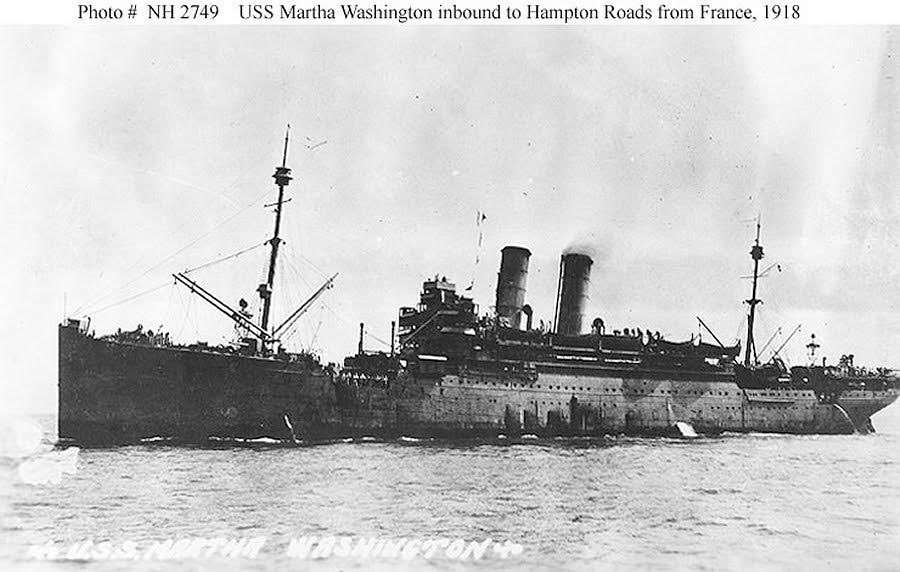

Miami County, Indiana, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,653,567. Image “USS Martha Washington (ID-3019).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 July 2018. Wilgus, William John. Transporting the A.E.F. in Western Europe, 1917-1919. Columbia University Press, 1931.

|

|

|

|